My guide, Rod Pinkston, a retired U.S. Army Master Sergeant and owner of Jager Pro, scanned ahead with a thermal scope, keeping an eye on the moving hog. I tried hard to keep my nose from crashing into his rear every time he stopped. When Pinkston took a knee and lowered his electronic ear muffs, I knew my time had come. Ever so carefully, the long, extended legs of the Harris bipod were lowered into position, and I took a knee in the soft dirt. A bright white light exploded into my eye, and after my iris adjusted, I could see a white-hot hog walking just out of my field of view. After shifting left and centering the pig in my thermal scope, I tapped a button and enlarged the scene three times. I put the simple reticle on the hog’s head and squeezed the trigger. Recovering from the recoil, I found the hog in a pile, kicking up a small dust storm after the 180-grain bullet crashed through its brain.

Unless you have had the distinct and expensive pleasure of replanting a peanut or corn field two or three times in the same year or had equipment break because of rooted fields, it is difficult to understand the nature and size of the South’s feral hog problem. The damage runs in the millions of dollars, and a persistent sounder of hogs can unhinge the shoestring finances on which most farms operate. When Pinkston retired in 2008 after a long and varied 24-year Army career that included training gold-medal-winning Olympic shooters for the Army Marksmanship Unit, he decided to help farmers, have a lot of fun and make a living doing it, and thus founded Jager Pro in 2006.

“I was sitting at an OP looking at enemy soldiers, camels and wild dogs during Desert Storm with thermal and night vision equipment and thought this would be perfect for solving feral hog problems,” Pinkston says. “When I got back to the States, I started to implement my plan.”

Pinkston acquired some very high end, military-grade thermal and night vision scopes. He also began to study and develop more effective trapping techniques. The end result five years later is a company that specializes in removing feral hogs by the ton. Jager Pro shoots and traps hogs, depending on the site, for anyone with a hog problem.

“Originally, I didn’t want to be a shooting guide, I wanted to be a hog control operator,” Pinkston says. “But we had to figure out a way to generate income, since most farmers don’t have the money for hog control. Taking shooters along with us was a great way to do that.”

Hog hunting start at a shooting range, where guys have a chance to confirm zeros and get familiar with the scopes, which are very simple to operate. Since the vast majority of hog activity is during the night, just after sunset Pinkston or one of his guides loads a utility vehicle with rifles, ammo and thermal and night vision equipment; attaches a small trailer for hauling dead pigs; and sets out on one of the many farms that have contacted Jager Pro for its services. Pinkston figures he has access to more than 200,000 acres in southwest Georgia.

The hog hunting season starts right after deer season ends in January and runs through the planting season, usually stopping in early June. Once the crops are up and growing, it is impossible to see the hogs, but just after the corn harvest starts in August it is time to pick up the rifles again. The shooting stops and trapping begins when Georgia’s firearms deer season starts in late October.

Pulling up to a field, Pinkston scans the darkness with a 640×480- pixel, long-range thermal spotting scope. The vanadium-oxide detector does not require any visible light and detects, then displays the different temperatures it sees on a small screen in the scope. The 320×240-pixel scopes mounted on the rifles operate the same way, so shooters are looking into the scope, not through it.

“We can detect heat signatures 11/2 miles away and actually tell what we are looking at as far away as a half mile,” Pinkston says. “I can cover a 100-acre field in about 30 seconds. The equipment allows us to cover a lot of territory and take the fight to the hogs. We don’t wait for them to come to us.”

Once a pig or pigs are located, the group maneuvers downwind and starts a stalk. Wind is by far the most critical factor, since hogs have one of the most sensitive, diagnostic noses in nature. Metallic clicks or talking would certainly alert hogs and send them into the next county, but quiet walking is ignored for the most part. Jager Pro does not schedule hunts on the 10 days surrounding a full moon to completely eliminate movement from the stalking equation. It also helps keep deer, another early warning system for the hogs, in the dark as to what is about to happen.

We usually stopped about 100 yards out to turn on our thermal scopes and then closed another 50 yards before lowering our bipod legs and setting up. Single hogs are pretty easy to take, and Pinkston just backs up his hunter. Sounders are a little more complex, but after two or three groups it is pretty easy to fall into a rhythm. Shooters come on line and target a hog. Pinkston counts down from three, with everyone firing on zero. After that initial salvo, the melee begins and shooters start picking off additional hogs. Pinkston or the guides also shoot, since the goal is to kill as many hogs as possible as well as act as safety officers.

“Hunter success relates directly to how well they shoot moving targets,” Pinkston says. “The guys who can shoot moving targets do pretty well and often kill over 20 hogs a night.”

Our second encounter was a great example of just how effective the equipment and shooting methods can be. Cruising to another corn field, Pinkston quickly spotted a 13-count sounder on the opposite end of the field. We closed the distance in the cart and then started stalking about 300 yards out. At 100 or so yards, I turned on my scope and scanned for the sounder. The hogs were milling around without a clue. I watched a sow work right down a row, picking out the freshly planted corn seed from the dirt she overturned with her snout.

We set up just 40 or 50 yards away on our tall bipods. Two hogs hit the dirt at the initial shot, and the 11 that were left exploded into all different directions. I missed my first follow-up shot but connected on the second. Pinkston was doing some serious work with his thermal-equipped DPMS LR-308L. When the shooting finally stopped, we had six pigs down in the field.

“Since January 22 of this year, we’ve killed 424 hogs in 36 nights with a 100 percent success rate,” Pinkston says. “Our goal is to kill 1,000 hogs in 100 or 110 nights of shooting annually. Weather is the only factor that limits our success.”

The farm where we were shooting is a familiar stop for Pinkston. It backs up to a 30,000-acre wildlife management area, most of which is river swamp and a breeding ground for feral hogs. Since 2007, Jager Pro has killed well over 1,000 hogs on the property. In the first six months alone, shooters killed 462 hogs, and 91 of those came out of just one peanut field.

“The owner told me he had to replant that field two or three times one year,” Pinkston says. “Now they have less than $500 of crop damage annually because we are knocking the population back. We save them about $20,000 to $25,000 on 2,500 acres. Using that one-two trapping and shooting punch, we are confident that we can knock the population back 90 percent in six months—enough to control their numbers.”

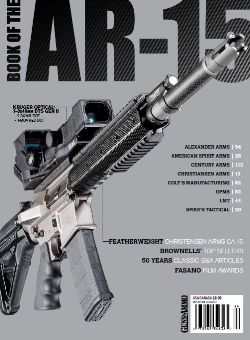

Pinkston is quick to credit the rifles as a key piece of equipment. After using several different makes and models, he settled on the AR-10. Detachable, highcapacity magazines and not having to run a bolt or pump make the AR-10 much more effective than other designs. We used a DPMS LR-308L and a Remington R-25. Since both uppers utilize 1913 rails, mounting the thermal scopes was pretty simple. About the only modification is adding a riser to the buttstock, since the scope’s eyepiece sits a little higher than traditional optics.

“We are more effective if we can use a high-capacity magazine, since the more rounds we can accurately get downrange, the more successful we will be,” Pinkston says. “Also, having a semiauto rifle vs. a bolt action is much faster. You can stay in the gun better and never lose the pigs in the scope, which allows you to pick up second, third and fourth targets easier.”

I am very familiar with both rifles, having hunted with them extensively for the last three years. Of the two, the DPMS gets my nod, though the R-25 looks pretty cool with its camo finish. The big difference, besides appearance, is the fore-end. The LR-308L has a free-floated carbon fiber unit that is light, quiet and neither cold nor hot to the touch, while the R-25’s aluminum tube can be a little noisy. Both guns had excellent triggers, and accuracy was good, too.

Being that he’s a salty old soldier, it should come as no surprise that Pinkston prefers the .308 over all other AR-10 chamberings.

“We usually shoot 180-grain Nosler Partition bullets in our .308s,” Pinkston says. “That cartridge and bullet will take down the bigger, 300-plus-pound boars we will routinely find and kill hogs from any angle. Most other AR cartridges won’t.”

Even experienced shooters might have a little trouble with the optics, at least on the first few stalks. The scopes are fitted with an accordion-like eye cup that, when depressed, activates the scope and collapses under recoil. Most of us are unaccustomed to having something attached to our face when we shoot, so it takes a little getting used to. Pinkston also stresses staying locked into the rifle, aggressively pulling the rifle into the shoulder and horsing it around to control recoil. That keeps the running hogs in the field of view so that it is not necessary to reacquire the pigs after each shot.

We managed to catch up with one last pig about 2 a.m., bringing our nighttime total to eight. Pinkston lamented that we had an off night, slow by his standards. I was pretty satisfied. Pinkston’s hunts, as you might expect from a senior NCO, are squared away and run like a military operation.

Thermal hog huntting is a new wrinkle in a familiar game, and it is easy to see how devastatingly effective Jager Pro’s methods are. We did a lot of trigger pulling that night and good work from a conservation standpoint. There were eight less hogs working their way down freshly planted corn rows and a couple of hundred pounds of pork in the freezer.

It’s Not Hunting, It’s Wildlife Management

Shooting is really not the right word for a night spent with Jager Pro. “Attempted eradication using sophisticated technology and the best firearms possible” would be a more apt description. Giving the hogs—a very destructive, invasive species—a sporting chance was never in the cards. For a lot of conservation minded hunters, it is a difficult concept to master.

Feral hogs are a controversial animal because they occupy drastically different places in the minds of different people. Farmers and landowners view them as a plague, while some hunters view them as a challenging quarry and magnificent trophy that deserves a lot of respect.

“It’s been really hard to get some hunters to understand what we are doing and why we must control feral hogs using these methods,” Pinkston says. “We get as much pushback from hunters as we do the animal rights folks. But we simply can’t treat feral hogs as a game species. We have a responsibility as conservationists to better control their numbers.”

Pinkston makes a valid point that using hunters to control hog numbers, as a game management tool, is probably one of the few things that nonhunters can understand. Hunters certainly do not need the approval of or validation from the nonShooting public, but in an age where shooting rights will be challenged in the court of public opinion, every little bit helps.

“If hunters aren’t the ones controlling hog populations, we will be replaced by government shooters in helicopters, chemical toxicants or contraceptives,” Pinkston says. “We, hunters, have to take the lead on this problem.”

So when Jager Pro leads a team of shooters into a field and they kill a dozen pigs in one night, they are not doing so to be greedy. They are helping farmers and, most important, playing a pivotal role in wildlife management.

Pile of Pork, Lots of Fun

To say that shooting with the latest thermal and night vision equipment in a target-rich environment where there is no limit makes for a fun night in the peanut field is the understatement of the year. These hunts are very exciting— and easy.

Jager Pro provides everything from rifles to ammo to places to hunt. The only equipment you really need is a pair of rubber boots, bug suit or ThermaCELL, and enough energy drinks to stay up all night. Electronic hearing protection is nice, but plain old muffs will work. Jager Pro has meat processors lined up to turn your quarry into a pile of pork chops and sausage if you so desire. Taking home the meat is not a requirement, though.

Hunts are generally two nights and run $2,200 for two hunters or $3,300 for three hunters, lodging included. If you would like to see what hog hunting looks like through the thermal scopes, go to JAGER Pro’s YouTube page. Pinkston has uploaded a bunch of videos that not only show hunts, but the proper leads, too.